Post-Punk, Futurepop, Post-Communism and The Melancholy of Bad Dancing

A Celebration of Belarusian Band Molchat Doma

In Belarus there are two ways to say “welcome:” Привет in the commonly spoken Russian language, and прывітанне in the less common, endangered Belarusian language whose status is not that different (though less endangered) than Irish Gaelic.

It is one thing to declare a proxy war upon a country (two countries: Russia and Belarus) and “cancel” their cultures as if they were social media users. (A cancellation which, in practice, means the language culture)

It’s another thing entirely for a cultural force to go against the grain and become more culturally prominent in the West…while using a cancelled language!

This is the first reason I count myself a fan of Belarusian Post-Punk trio Molchat Doma from Minsk, Belarus. One of the more recent (relatively speaking) signatories to my favorite music label, Sacred Bones Records. To enjoy their music, click below to listen while reading the rest of this post. (As I’ll explain in a bit, album-centered listeners should check out Etazhi)

(By pure coincidence, they released their first live album just yesterday: Live at the Panorama Hotel. Though since it contains three tracks, it would be more accurate to call it a live EP.)

I say post-punk because being seasoned on punk and being a long-time fan of post-punk groups like UV Pop, Sad Lovers & Giants and of course Joy Division, that is my first frame of reference. But one can just as easily call them a cold wave, futurepop (90s-early 00s synth pop/goth offshoot), minimal wave or even new wave group. Apart from new wave (which is rarely dark) Molchat Doma songs exist in a perfect state of integration in all the playlists I’ve made of the aforementioned genres. Even if the songs were recorded thirty years before Molchat Doma even existed.

While their music is dark, it is unusual in that it is dark music with something for everyone; defying all cultural and socio-political odds, Molchat Doma is unusually (and beautifully) accessible. This, incidentally, was a major factor in making classic post-punk popular in the 80s. In particular, by innovating a more danceable variant most famously represented by the New Order song “Blue Monday 88.” Bands/groups like New Order, Soft Cell, Xymox and many others came to understand that dark music was much more accessible if it was danceable. They were right, as its popularity indicated.

Molchat Doma understands their roots very well, enough to where dancing is one of their conceptual themes. (More on that later in this post) But creating music in the 2010s, with a much more compartmentalized population from which to cultivate a fan base, presented, no doubt, a challenge of its own.

If we draw from literature, Isaiah Berlin’s fox/hedgehog dichotomy presents a path forward in these instances. The path of the fox is compartmentalization: separate the post-punk, cold wave, etc. and record either separate albums or use different artistic project names. For what it’s worth - and they’ve more than proven its worth - Molchat Doma has chosen the path of the hedgehog. Some songs are more post-punk, some are more minimal wave or futurepop. But they are all extensions of the basic Molchat Doma sound. (This is also less unusual when one discovers that major futurepop artists usually don’t reinvent the wheel very much)

Comprised of vocalist Egor Shtutko, guitarist and drum machinist Roman Komogortsev and bass guitarist Pavel Kozlov (the latter two handle the synthesizers), Molchat Doma’s first album, S krysh nashikh domov (“From The Roofs of Our Houses”), has been described as dark music that was “bashed out in a Cold War bomb shelter during the early '80s.”1 Though that description might sound stereotypical, the band themselves leaves little doubt as to that theme with their slow, seemingly indifferent yet surprisingly anthemic “Ya Ne Kommunist.” (I’m no Communist) An essential song for any and all counter-revolutionaries wherever you may roam.

As one might expect from a debut album by a group with such specific origins, S krysh is the most Belarus-centric album as well as the most unabashedly post-punk. (Which is another way of saying it’s the least danceable) Allmusic stresses the very strong anti-social character of the albums songs, which - paired with a dystopian mood Belarusians and everyone beyond the border can hone in on - sets Molchat Doma apart as one of the few musical artists genuinely concerned with alienation at a time when that theme is lyrically (if not quite melodically) out of vogue in the West. (This being so that society can try and trick the populace into believing their alienation, now the norm, is a net positive) Though not their strongest creation, certain songs on S krysh (like “Kryshi,” “Pryatki,” my favorite “Ludi Nadoeli” and “Doma Molchat,” the eponymous song that first anticipates their futurepop direction) absolutely belong on a greatest hits if the trio (or their music label) ever considers such an endeavor.

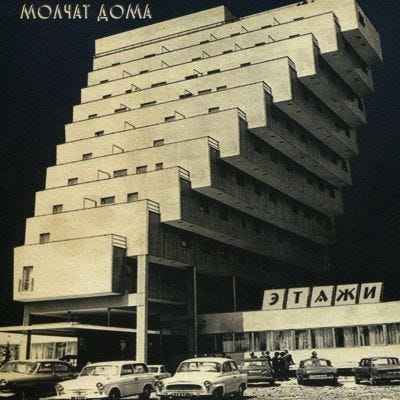

Whatever the response to the album in Belarus (and social media did a lot to spread the word from here on out) Molchat Doma was just getting started. Only a year later, they released their thus-far best album, Etazhi. (2018, “Floors”)

As Allmusic points out, a part of the reason Etazhi was a step up had to do with improved production in their “bunker” of a bomb shelter. Even so, Etazhi wasn’t a departure from their old sound, but - like the early Ramones albums - an improvement of what they already had. And it was more than just production.

Molchat Doma was wise to do this: if music historians stress one thing about the “indie scene” of the 2010s, it is the pursuit of some semblance of originality at all costs, which often means abandoning something that isn’t broken only because it sounds a bit too similar to someone else. (I think of The Head & The Heart, a talented folk rock group that, after two excellent albums, dramatically switched styles into a weird, indietronica/folk mush; though this was in large part due to the departure of one band member, I suspect that comparisons with The Lumineers (which must have been frequent) might have had something to do with it) Great potential was wasted by this indie scene approach: fortunately Molchat Doma didn’t fall for it. Any obvious link to previous post-punk, synth pop, cold wave, etc. was more than compensated for by the chemistry of talent and the fact that, unlike so many musical artists today, Molchat Doma actually had (and still has) something to say.

While the whole album is worth a listen, highlights include “Prognoz,” (my favorite if I had to choose) “Kommersanty,” “Toska,” “Kletka” and the song I consider their most definitive on an equally definitive album: “Tancevat.” Another song, “Sudno (Boris Ryzhy),” is noteworthy as a tribute to Russian poet Boris Ryzhy while “Kommersanty” complements, in coin-like fashion, “Ya Ne Kommunist” by being about the ruthlessness of business-world revisionist propaganda and its quest to reinvent history. (Something I often criticize on my other Substack, Timeless, though not always from a commerce angle) I sincerely hope a Polish band covers this song with Polish lyrics, covers it well and plays it on all the airwaves; we need more songs like this in every language.

“Tancevat” is about that which most of us are genuinely talented at doing: dancing badly while still finding solace and meaning in the act of losing ourselves. Though some might resent such an interpretation, it is symbolic of the Christian (Orthodox?) ghost in the post-communist, globalized machine. When it comes to singing in the West, there are two places where we are “allowed” to sing badly: 1) an Irish pub, and 2) at church. While it’s true that at church a talented choir usually compensates for any bad singing on the part of the “flock” (just as a talented Irish folk band does the same at a pub) it is an expression of the average Christian’s understanding of themselves as a less-than-perfect sinner who, nonetheless - and unlike Cain - presents himself or herself, like Abel, to God with all our flaws. “Tancevat” is not about Bolshoi ballerinas but the dancing of the Good Thief.

“Tancevat’s” gloomy celebration of bad dancing is revolutionary in our era when dancing is one of the few talents Americans don’t bring others down about, Harrison Bergeron style.2 Molchat Doma’s atmosphere is inherently dystopian, and in most dystopias (especially Communism) genuine talent and artistry has been liquidated. (While dancing is often used to compensate for turning the country into a cultural wasteland; the Chinese, for instance, are known to use dancing troops of indoctrinated Uighurs to convince the world that everything’s fine and that there’s no genocide to be seen) As “good dancing” is the property, if you will, of the dystopian power, bad dancing therefore becomes the same kind of escape (not to mention political act of resistance) that the “lying down” movement in China has become in recent times. (In that case, lying down is the opposite side of the spectrum from “working hard” for the CCP) If a similar “bad dancing” movement started (though it would have to be aesthetically careful) and traced its origins to “Tancevat,” it would be a beautiful manifestation of Slavicness in the wider world.

Etazhi must have made a lot of waves in the Russosphere as the band soon attracted the attention of Sacred Bones Records. This is the first turning point in their career as it paved the way for prominence and success in the West, with 2020 being what Allmusic called “their breakthrough year.” (Amplified, no doubt, by covid lockdowns that must have made their “bomb shelter music” a lot more relatable) A reissuing of their first two albums for general consumption in the West led to their third album, Monument.

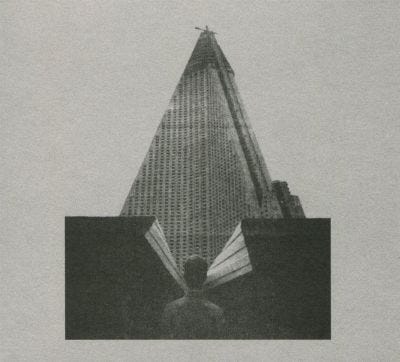

As one can see from the cover, Monument as a title is not a concession to English but simply a Russian word that happens to be the same in English. Perhaps that still counts as a concession to some, but it would be more accurate to say the band met their new, non-Russian speaking fan base halfway without compromising on all that made them what they are. As they should have.

If the artwork clearly hearkens back to Etazhi, the music has changed considerably. The trio channeled the futurepop/synth pop side of their artistry in a way that almost repeats the evolution of post-punk into danceable post-punk. While it may well be that musical logic can only go in the same directions as before - that something in post-punk’s basic artistic DNA inadvertently leads towards danceability - this development is also in keeping with the band’s artistic development in the lyrical sense. But while the departure is huge, it isn’t radical: here, too, Molchat Doma’s wisdom prevails.

It may be that Monument works a lot better on a turntable than in a digital format: now that I am able to play vinyl records again, I intend to put Monument to the vinyl test once I get ahold of a copy. But while Monument doesn’t have as many good songs as Etazhi, those that are good are not just good but outstanding as a result of the extra studio polish and the upgrade to danceability. The best song on Monument (and one of their best songs period) is “Discotheque,” a sequel to “Tancevat” with the capability of conjuring bliss in the heart of every Depeche Mode fan. But other highlights include “Utonut,” “Zvezdy,” “Otveta Net” and “Udalil Tvoy Nomer.”

Already, Molchat Doma had more good songs for a greatest hits album than even most legendary classic rock artists did at that time. (To cite a couple of my favorites at random: Jethro Tull hadn’t even released Aqualung and Blue Oyster Cult was still an album away from Agents of Fortune and “Don’t Fear The Reaper”)

During this time, the band also released one of the most outstanding covers I’ve heard in a long time: a cold wave/darkwave version of Black Sabbath’s “Heaven and Hell” with Russian lyrics. Incidentally, this was the first Molchat Doma song yours truly ever heard; by the time it was over I was a fan without question. It wasn’t just an outstanding tribute to a band that, in general, requires real quality to match their stature (as is the case with Black Sabbath): “Nebesa i Ad,” as the Russian version is titled, was just as much an anthem of reinvention as it was a tribute to nostalgia. The best of both worlds and a formula so rarely seen in music that hearkens back to more “venerable” genres.

Studio-wise, Molchat Doma lay quiet for a time after that. A new fan base in the West meant new musical responsibilities, like tours that led to a 2022 performance at Coachella, among other noteworthy music festivals. But finally, last September, Molchat Doma got around to releasing their fourth album, Belaya Polosa. (2024, “White Stripe”)

And this time, Molchat Doma did, indeed, take a radical departure. (Which is also where we get to one of our Černobog's Shadow themes)

Belaya Polosa’s cover art, though in the same “architectural” genre, immediately stands out for its color. And that is no coincidence. During this time the band relocated to Los Angeles (I hope they’re all right given the fires going on right now), a radically different environment from Minsk to put it mildly. (One recollects Star Trek: Next Generation where the Klingon Worf, adopted by Russians on Earth, suggests Minsk as a tourist destination to some aliens curious about Earth; a remark intended as a joke at Worf’s expense since (wink wink) “who wants to go to Minsk?” A classic pop culture leftover of 90s condescension that, sadly, accompanied the just celebration of the vanquishing of Marxism-Leninism and that also makes one of my old 007 movie favorites, GoldenEye, increasingly unwatchable as time goes on)

I suspect one of two things happened: 1) when looking for a place to live in LA, Molchat Doma crashed with a futurepop junkie whose living room soundtrack so permeated the very firmament of that home’s existential focal point in the universe that the band couldn’t successfully re-establish their balance; or 2) someone in LA who lives by the “happy directive” (and there are many such types in LA) and who doesn’t understand cold wave or post-punk heard the band’s music and said “like, oh my god; you guys need like more color in your music.” And since Americans love to “instruct backward Slavs” on pop culture, such a scenario is very, very easy to imagine. Still, other factors are worth considering: perhaps the good people at Sacred Bones wanted Molchat Doma to do the same thing their longer-term artist, Zola Jesus, did with her pop album Taiga (though with respect, they are fools if they did such a thing); or maybe, with war breaking out in the region in between Monument and Belaya Polosa, Molchat Doma felt their sound had to be “less Belarusian” and “less Russian” this time around to avoid any mistaken interpretations of wartime sentiment.

Whatever the reason, Belaya Polosa is their first homogenous album since S Krysh; where their debut was near-pure post-punk, Belaya Polosa is for all intents and purposes a futurepop record with a more explicit relationship to its original synth pop sources than artists like Assemblage 23 and Apoptygma Berzerk dared to reveal back in the day. Though it is the least strong album they’ve recorded, the transition (unlike Zola Jesus who, wisely, eventually abandoned the Taiga transition and returned to her darker, “industrial synth pop” sound) is successful here. For better or for worse.

The upside is a deeply nuanced and sophisticated, if uniform, production and sound than ever before. It is some of the richest synth music I have heard in a long time outside of the synthwave sub-genre. The downside is that not a long of the songs on Belaya Polosa are as good as their previous albums.

In my mental greatest hits collection I would only add “Ty Zhe Ne Znaesh Kto Ya,” “Son” and “Kolesom,” though I personally also like the song “III.” Not a lot but still: enough to give Molchat Doma, after only four albums and a few non-album singles and tracks, enough content to compile a Greatest Hits comparable to Depeche Mode’s fantastic Catching Up With Depeche Mode. (For those who don’t know, this is the best anthology of Depeche Mode’s earliest work; the era of “Blasphemous Rumours,” “See You,” “Dreaming of Me” and “Can’t Seem To Get Enough.”)

Despite its shortcomings, however, Belaya Polosa is not an album to be ashamed of. Though not Etazhi, it is a most welcome album and an interesting (I hope) stylistic side trip. Bands have zeniths and nadirs all the time and fans tend to be (or should be) patient with the bands they like. But compared to what they’ve released before, Belaya Polosa falls into the nadir category. And the trio should be aware of that as they prepare for their fifth album.

Here we come to the real reason I wrote about the band here. (Apart from promoting the juicy fruits of the Slavic world)

Despite appearances, Belaya Polosa is NOT Molchat Doma “selling out.” Unlike punk rock, “selling out” isn’t about switching from your local label to Warner Bros or making one’s sound more mainstream to be popular. That is a 20th century formula that has nothing to do with the near-total marginalization of music in the AI/Taylor Swift era.

The real metric for “selling out” is globalization. Meaning: singing in English, creating servile imitations of Anglo-American styles, denying your entire local heritage in order to become a babu, and so on. “Western Europeans” (and, increasingly, West Slavic nations) do it all the time and (apart from metal where the rules are a little different) it’s absolutely pathetic. If Molchat Doma really wanted to “sell out,” the way to do that is to switch to English. I was annoyed when one of my favorite Neo-Folk groups, DakhaBrakha from Ukraine, briefly recorded a couple songs in English a while back. But to their credit (and this probably due to their huge following in their home country where they are almost an institution) that appears to have been nothing more than a flirtation. I wish I could say the same about so many musical artists west of East Slavia.

Belaya Polosa is a radical style switch that may or may not be in Molchat Doma’s best interests; in my opinion, they need to recover some of their original sound on their fifth album and use what they learn here to make an albym that’ll knock everyone’s socks off. But despite their being in LA, Molchat Doma hasn’t switched to English. Nor (if the music video for “Ty Zhe Ne Znaesh Kto Ya” is any indication) have they abandoned their most pertinent artistic themes. Both of these keep Molchat Doma grounded so that they don’t forget where they came from. Because where they came from is what makes them special. People like they because they are different. That’s why they’re awesome.

Again, if either Egor, Roman or Pavel reads this, we here at Černobog's Shadow implore you: DON’T SWITCH TO ENGLISH! Do not “fix” what is not broken. Do not listen to the words of the Allmusic review where they condescendingly say that your lyrics are “still written entirely in Russian;” as if that’s something dated one has to be ashamed of and forgo. That is nothing but the falseness of American pretension. NEVER surrender to Anglo-American pretension. Least of all when you don’t have to.

Here we come to one of the most amazing things about Molchat Doma’s success: at a time when it is culturally acceptable and even encouraged to hate everything Russian (including the language) Molchat Doma’s music defies that which might otherwise seek to drag it down.

For those who hate base prejudice, Molchat Doma (and not America’s rich race activists) is the success story of our day the way Rodriguez’ music was in apartheid South Africa in the long run. I don’t think I need to tell a band from Lukashenko’s Belarus how to maneuver the relationship between their artistry and politics. But for the love of God (again, if the band is reading this) don’t lose track of what the success of your music says in this respect.

In other words: don’t lose track of yourselves. I don’t believe I speak only for myself when I say that I, and many others, will remain devoted fans. Switch to English and you will lose them.

https://www.allmusic.com/album/belaya-polosa-mw0004311692

This is in large part due to the dictates of race pathology. In America, good dancing is intrinsically associated with Black people (even though there are many Black people who are lousy at dancing) and in race pathology logic, bad dancing = racism because bad dancing = White people, especially the “Protestant work ethic” White people who were, admittedly, anti-dancing in the Colonial Era. If the above logic hasn’t yet been taken to the conclusion laid out here, it’s only because race pathologists haven’t yet felt the need to take it there as of yet.