First things first: welcome to Černobog's Shadow, everyone! I thought of posting a bunch of preliminary stuff. Then I changed my mind. The one thing I should say is this: while my own expertise is a bit lop-sided, I will do my best to represent all Slavic nations on this newsletter. I can’t promise everyone will agree with everything: but that’s a stupid promise to make, isn’t it?

To prove it, I decided to start with a nation we don’t hear enough about: the Slovaks. As the Slovaks like to say: Vitajte!

So without any further ado, let’s begin! Be sure to like, comment, share, etc.

Ján Johanides was one of Slovakia’s foremost postwar authors. Disgraceful as it is that he is only now translated into book form in the English language, you know what they say: better late than never.

Inevitably, however, suspicious people will wonder: why wasn’t it translated sooner? And what does that mean?

While I think such thinking is unnecessarily uncharitable - Johanides is well worth reading for anyone with standards - to non-Slovaks our author is nothing more than a name without context. Context we here at Černobog's Shadow are more than happy to elaborate upon for yours truly. Especially given the outstanding quality of the translation, as expected from the one-and-only Julia & Peter Sherwood.

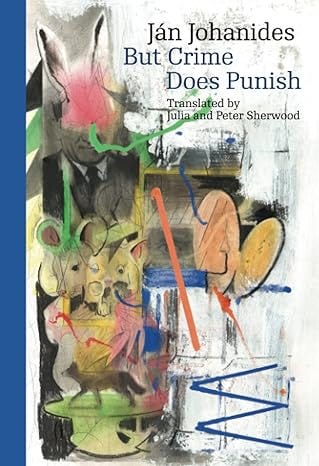

Originally published in 1995, the recently translated But Crime Does Punish (Karolinum Press, 2023, original title Trestajúci zločin) is a latter-day novel in what has been a long authorial career. (His first novel came out in 1963) Ironically, it would have been among the first published in the independent country of Slovakia. This is fitting, given that But Crime Does Punish tells a Slovak story through and through, even if its influences are international.

While structurally But Crime Does Punish owes much to Johanides’ former countryman Bohumil Hrabal - especially the masterpiece Dancing Lessons For The Advanced In Age - the back description also cites Carlos Fuentes and John Le Carré as important. While Fuentes fans can judge for themselves, the Le Carré comparison is remarkably accurate as But Crime Does Punish - a multifaceted creature in so many respects - has the atmospheric character of a Le Carré spy thriller but with an artistic bent that owes more to the literary exploration of memory than the in-the-moment intensity of Leamas’ mission in The Spy Who Came In From The Cold. (Though not, in Johanides’ case, at the expense of intensity)

An interesting question I had in mind when opening the book is: why, of all his books, did the Sherwoods pick this one as the first to enter the English language? It isn’t his best-known book in Slovakia: that, according to the afterword, is an historical novel from ten years earlier titled Marek koniar a uhorský pápež (Marek the Horseman & The Hungarian Pope). To be sure, the historical novel doesn’t appear to explicitly represent the shared themes of Johanides’ greater oeuvre. But the same afterword traces Johanides’ story as a quest from the moment of his birth to the publication of But Crime Does Punish, suggesting the Sherwoods saw this novel as the peak Johanides spent his career trying to reach.

The lame thing about this is: it risks suggesting that Johanides’ other work is not worthy of being translated (Personally, I hope that’s not true) But on the bright side: But Crime Does Punish is, without question, great literature. If not a masterpiece, it is a gem. And in literature, the word “gem” is synonymous with “little, maybe idiosyncratic, masterpiece.”

Cormac McCarthy once said that literature uninterested in the exploration of life and death isn’t good literature. While Johanides’ work is no stranger to death, it (quietly and without moralistic language) explores the other side of that graph: good and evil, with a strong focus on the latter. While Johanides’ originality isn’t immediately evident to most readers, our author is at his most original in this respect.

Ondrej Ostarok - the Hrabalesque (though not purely) narrator of our story - was a bureaucrat who, beforehand, was sent to the notorious Valdice prison after his father, the leading Communist in his Central Slovak hometown, made a drunken ass of himself. In Valdice, our narrator ends up castrated after refusing the advances of a homosexual prison guard. But Crime Does Punish is, as a result, a formative novel of the Genitalist movement that predominated in Slovakia in the 90s and whose influence still lingers. And Ostarok’s empty scrotum haunts the novel from start to finish. (Especially its function as a state secret)

Hired afterwards as a bureaucrat to manage an archive full of secret police files - which is where the Le Carré side of things kicks in - the novel, through the distortions of memory, sophisticatedly adopts themes of emasculation, the legacy of evil and whether there was ever any good to speak of in the Communist system. (And, in a greater sense, the legacy of Slovak history in general) Based on what I’ve already read in translation, But Crime Does Punish is the best of Slovak Genitalism in that the emasculating concepts explored here are successfully integrated into the greater discussion of good and evil. The results are both what one might expect and not what one might expect at the same time. (And, I might add, deeply relevant for the trials and tribulations of our own time)

It is worth noting that But Crime Does Punish, despite the history it deals with, is not an anti-Slovak novel just as it is not a “moving paean of hope.” Those looking for a tearjerker about how evil the Communists were (or Tiso for that matter) won’t find that here; though this is a must-read for those interested in the problem of evil, it is not for the sentimental. But it is, without question, one of the best Slovak works of fiction in English translation. And one of the few rendered into English by equally talented translators.

Given that not a lot of Slovak literature is in English - nor is it easy for Anglophone readers to easily get a sense of Slovak literature’s chronology and changes, though it shares some developmental trends with the Hungarians and Czechs - outside of Slovakia But Crime Does Punish is most similar to the post-Velvet Revolution works of Pavel Kohout (I Am Snowing), Ivan Klima and Jachym Topol. Though contemporaneous with the latter’s postmodern monster - City Sister Silver - it shares a resonance with Topol’s later satire, The Devil’s Workshop. Nowadays a go-to book in courses on the region’s literature as a definitive specimen of post-1989 regional literature.

But where Topol is content with using the historical memory of Terezín and the Holocaust for satirical purposes (at the sort-of expense of the Belarusians), Johanides goes deeper. Unlike his Czech counterparts, Johanides is genuinely sincere in trying to obtain some kind of resolution for this horrid chapter of Slovak and Czech (and, indeed, Slavic) history. Thankfully for us Slavophiles, Johanides is as uncompromising in both atmosphere and imagination as he is sincere. And the Le Carré influence also means that Johanides, while never low in the artistic department, has authored a story that readers of “conventional” literature can access, albeit in roundabout ways.

Together, this makes But Crime Does Punish one of the best - if not the best - post-1989 novel from a Slavic nation to reckon with the Communist past. Not only is it masterful. It avoids all sorts of agendas that many post-1989 authors have, sadly, allowed themselves to succumb to: be it the insufferable, snobbery-ridden ego of Olga Tokarczuk, the unserious (though funny and qualitative) satire of Topol or the unrepentant, post-Yugoslav self-conditioning that defined the work of Dubravka Ugresic. (Viktor Pelevin is, perhaps, one of the few to successfully strike a balance between storytelling and a dash of agenda)

Johanides avoids all of that: and God damn is it refreshing!

Johanides is most welcome in English. I hope more of his work will come out soon.